On Friday, May 14th, AHRC New York City and its partners presented “A Call to Action: Eliminating Compounded Disparities for People with Disabilities in a Year of COVID,” a day-long symposium bringing together national leaders in health equity and policy to discuss the intersectionality of disability, race, ethnicity, culture, gender identities, and the political determinants of health.

Marco Damiani, CEO of AHRC New York City, said “COVID-19 has been a worldwide scourge for over a year now. Millions have suffered terribly. The pandemic has also laid bare the gross inequities experienced by people with disabilities and, in particular, people of color with disabilities. Today is an effort to better understand some of the root causes of this discrimination, the real-life impact on people, and to propose what needs to be done going forward.”

New York’s Senators, Chuck Schumer and Kirsten Gillibrand, each provided greetings, thanking AHRC NYC staff for their resilience throughout the pandemic and outlining recent legislation providing funding for key disability services, such as for home and community-based services (HCBS).

“We simply cannot return to the way things were before,” said Senator Schumer, the Senate Majority Leader. “COVID-19 put a magnifying glass on so many inequities and injustices that existed long before the pandemic.”

Keynote: The Political Determinants of Health

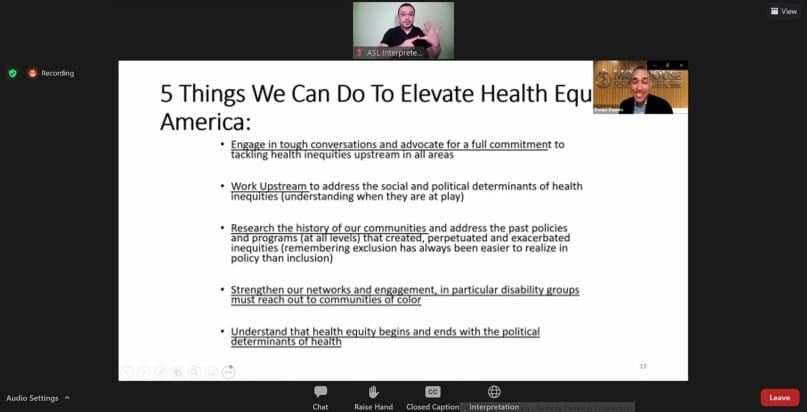

Daniel Dawes, a nationally recognized health care attorney and administrator who serves as the executive director of government affairs and health policy at Morehouse School of Medicine and as a lecturer of health law and policy at the Satcher Health Leadership Institute, provided the symposium’s keynote address tracing the historical origins of the political determinants of health that led to ongoing systemic discrimination against marginalized populations.

“Many racial and ethnic minorities, people with disabilities, and other vulnerable marginalized groups…struggle to live in a society that has intentionally erected barriers to weaken their bodies and hasten their deaths,” Dawes said. “These groups have experienced inequities throughout the life course—from womb to tomb.”

Dawes used the allegory of a society fishing together on the banks of a river, where “the health inequities that we face are represented by the bounty and quality of the fish that we encounter.” Different people having access to different types of resources represents the social determinants of health, while upstream decisions have downstream impacts. All told, the poor healthcare outcomes experienced by marginalized populations are “not an accident, [but] an act of policy,” said Dawes.

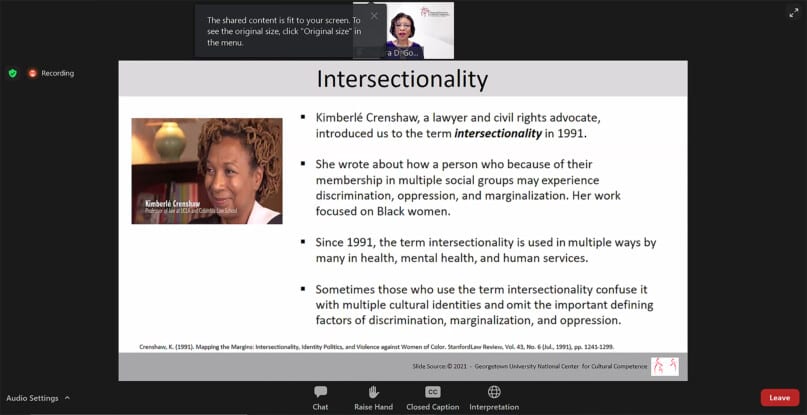

Dr. Tawara Goode led a panel discussion reflecting on Dawes’ presentation, agreeing with the message that people with disabilities require justice to account for centuries of neglect. Activist Lydia X. Z. Brown said, “Everything that affects our lives is considered niche and optional when for our lives it affects our survival.”

“Conversations that people with disabilities have been asking to have for decades are finally starting to be heard,” said Britney Wilson from New York Law School. Addressing intersectionality, Britney said that Black disabled people and Black people, in general, put themselves on the line in many ways during the pandemic, especially when it came to protesting the murder of George Floyd and others. “People of color, in the middle of the pandemic, risked their lives in terms of COVID and in terms police brutality in order to address injustice. The risks that we had to take were not the same.“

Lived Experience, Government’s Role, and the Way Forward

When most of New York City shut down in March 2020, government and other essential services including AHRC NYC continued without interruption due to the unwavering commitment from dedicated employees. The symposium’s second panel focused on “Lived Experience: Communities of Color, Disability, and the Physical and Mental Health Impact of COVID-19.”

Jennifer Natera, a Residence Manager at AHRC NYC’s Armstrong residence in Queens, spoke frankly about the physical and mental toll the pandemic took on her, her colleagues, and the people she supports. She said that frequently shifting medical guidance, staffing challenges including the loss of beloved coworker to the virus, and inadequate communications with healthcare professionals factored into an enormously stressful and transformative year.

“Every day I’m still trying to process what happened, personally and professionally. I don’t know the extent, but I do know it has strengthened my advocacy, my calling, my position, and hopefully this will be the last pandemic we ever go through and I don’t have to use this knowledge again in the future,” Jennifer said. Dr. Sheryl White Scott added that “credible data with diverse representation” will be critical to ensuring more equitable health outcomes.

In the third panel of the day, focusing on the government’s role in managing and preventing future pandemics, Victor Calise from the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities made note that NYC government services were never interrupted, including accessibility initiatives such as ensuring ASL translation at every mayoral press conference. Andy Imparato of the White House Coronavirus Task Force said “More people with lived experience need to work in government to address these issues. We had fights during this pandemic that did not have to be fights because with lived experience were not at the table when decisions were being made.”

Data was also cited by the fourth and final panel as part of “The Way Forward.” Devi Thomas from Salesforce said that “Data can be used leverage reform and justice, not just statistics on COVID deaths and money lost,” and encouraged organizations to leverage corporate and philanthropic partnerships that are similarly committed to justice.

Marco Damiani said that lack of technology created numerous barriers to receiving services for people with disabilities. Activist Judy Heumann called on higher education to take a more active role in disability justice by making concerted efforts to increase disability studies coursework. Finally, Tawara Goode said that change begins when visibility increases: “We need to change hearts and minds. In absence of close contact with any given community or group of people, stereotypes are likely to endure. Persons with disabilities have to be visible in our policies, in our society.”